Profit and the planet: the unlikely relationship that influences climate change

Author Jane Gleeson-White explores the relationship between economics and sustainability – and why we need to reset the current system.

Governments and corporations are currently set to value economic growth and profit over society and nature.

But for thirty years people have been working hard to change these systems: to extend the default settings of business and government beyond profit and growth to include the value of people and the planet. They're using the power of accounting and the law to make these new ideas and values central to decision making at every level.

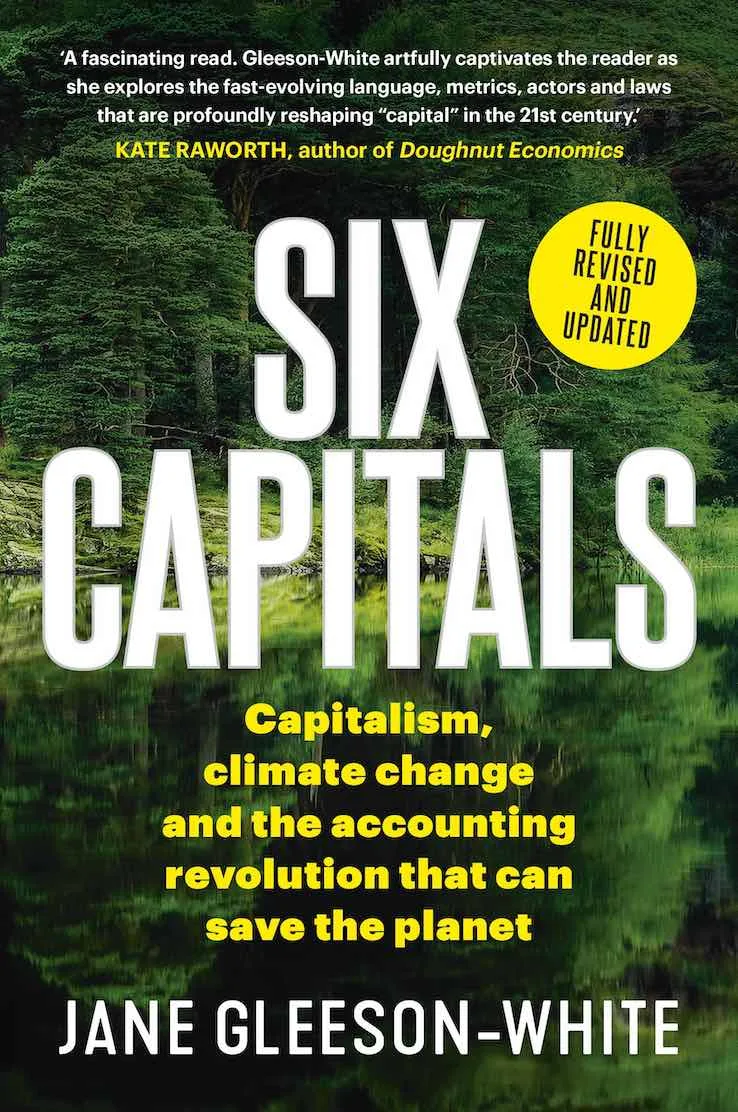

I tell their stories in my book the new, updated edition of Six Capitals – a book for everyone interested in the way we think about money, value and the way we organise our businesses and economies for the turbulent years ahead.

Some are creating new corporations, like Certified B Corporations, which balance care for their communities and environment while also making a profit. Leading local examples include Bank Australia, Australian Ethical, Future Super, Sendle and Who Gives a Crap.

Others are making new economic measures to include the wealth of nature in government policymaking and national GDP (gross domestic product) accounting.

Costa Rica is a good example of leading the way with this approach. It's been successfully measuring its natural wealth to direct government policy and protect its forests since the early 1990s. Since the program was launched in 1997, not only have Costa Rica's forests and natural areas been protected, but large tracts of ruined land have also been restored. In the late 1980s, only 21% of Costa Rica was covered by forests. In just ten years this had risen to 52%.

The increased forest cover also led to improved living standards and energy savings. In 1985, only half of Costa Rica's energy came from renewable sources. By 2010, this figure had risen to 92%.

The lesson that Costa Rica's policymakers learned from counting the value of living forests is that there's no long-term economic growth without protecting the health of the ecosystems. Economic and social health depend on the health of nature.

We're all learning this lesson now.

Right now the collective pause of coronavirus is giving us the opportunity to reset the way we do things, including the way we organise our lives and systems.

For example, the city of Milan in Italy has announced it will open city streets for cycling and walking that were once crammed with cars. Amsterdam has committed to "doughnut economics", a new compass for human progress that meets the needs of everyone within the means of the planet.

But this is a once-in-a-lifetime chance. We can do more than just adopt single initiatives and a new compass. Now is our chance to switch the default settings of the global economy and the way we do business to include the things that really count but are not yet counted: the wellbeing of our communities and our parks, beaches and open spaces.

When I was writing my book about the history of modern accounting which started in Renaissance Venice, I was shocked to discover that our systems haven't changed much in 500 years. Today that's a huge problem. Our accounting systems aren't designed for the 21st century global economy.

I was even more shocked to discover that because accounting reduces everything to its monetary value, it's allowed us to value the source of life itself, our planet, at zero. Through the logic of accounting, we've allowed the earth's living systems to go to ruin.

But I also discovered that many people were beginning to use the logic of accounting to address this. As the Guardian's global environment editor Jonathan Watts put it:

"So it has come to this. The global biodiversity crisis is so severe that brilliant scientists, political leaders, eco-warriors, and religious gurus can no longer save us from ourselves. The military is powerless. But there may be one last hope for life on earth: accountants."

I began looking into how people were using accounting to fight for nature and society – and that led to me writing Six Capitals.

If I've learnt one thing from writing two books about accounting (and seven years discussing the problems that bedevil contemporary accounting) it's that it's ultimately about value: accounting is the way we define and measure value and translate it into numbers and money.

And "value" is a very fuzzy, ill-defined concept that has changed over the centuries. So I can't overstate the significance of our much-overlooked accounting systems and the laws that underpin the global economy. It's time to fix them.

Coronavirus is changing the way we live, work, think, connect and entertain ourselves. It's showing us the power of nature (a virus) to interrupt our lives – and how much we need nature: the parks, gardens, beaches and rivers where we're now playing, exercising and finding comfort.

And coronavirus is teaching us how interconnected we are, how much we need each other and how important strong communities are to our physical, emotional and mental wellbeing.

As I discovered, all these things count for nothing in the systems that currently govern us. Businesses and governments are programmed to put profit and economic growth over communities and the planet.

This year has shown us that there are more important things than profit and economic growth. Let's make sure these values count when we rebuild our economies.

Jane Gleeson-White is the author of Six Capitals, Capitalism, climate change and the accounting revolution that can save the planet (Allen and Unwin, May 2020. RRP: $24.99).

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article (which may be subject to change without notice) are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Finder and its employees. The information contained in this article is not intended to be and does not constitute financial advice, investment advice, trading advice or any other advice or recommendation of any sort. Neither the author nor Finder have taken into account your personal circumstances. You should seek professional advice before making any further decisions based on this information.

Read more Finder X columns

-

All the big savings account interest rate rises: ING, AMP, Westpac + more

6 Feb 2026 |

-

Australian credit card debt soars 10% in a year: How can you escape the trap?

6 Feb 2026 |

-

4 cashback home loan offers to ease the pain of RBA rate hike

4 Feb 2026 |

-

Finder’s RBA Survey: Easing cycle ends as RBA delivers first rate hike since 2023

4 Feb 2026 |

-

Ubank Save is increasing its bonus rate up to 5.35% p.a.

3 Feb 2026 |

Image credits: Getty Images, Supplied (Jane Gleeson-White; photographer Sally Tsoutas)

Ask a question