12 reasons why Australia is heading for recession in 2020

It's the end of the world as we know it (maybe).

If you spend any time browsing this week's newspapers it won't take you long to find stories warning of a forthcoming financial Armageddon. Indeed, if you've been following the general economic news over recent months, it can feel like the alarm bells have been building to a deafening crescendo of talk about an impending recession from some experts for quite some time. However on the flipside, there are still plenty of arguments that this predicted financial armageddon is really just a storm in a teacup.

So who, or indeed what to believe? When it comes to a definite answer it seems that the jury (or in this case the financial indicators) are split down the middle. In this piece, I'm examining the main indicators that Australia should expect a recession in the coming months.

Wage growth has stalled

A growing economy relies on healthy consumer spending. This, in turn, is dependent on multiple economic metrics including stable employment, immigration and wage growth. Put simply, if people have more money in their bank accounts, they will spend more. This increased spending creates more jobs – which allows more people to be employed and wages to increase further.

While the Treasury forecasts a reasonable 3% Australian wage growth for 2020-21, it's looking increasingly unlikely that we will see it. June's ABS wage growth figures show a sluggish 0.6% growth in the last quarter, adding up to a total of 2.3% growth over the year. These results follow a five-year downward trend.

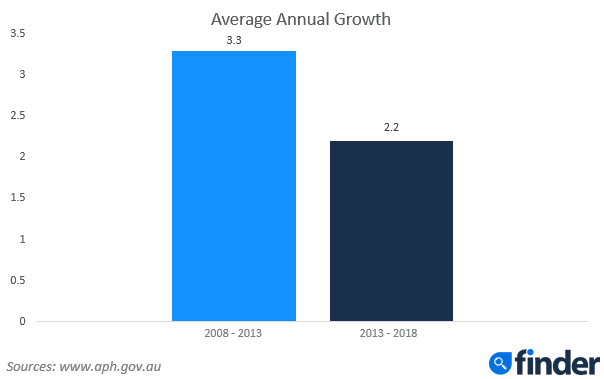

According to a Parliament of Australia report released in April this year, the average annual growth in real wages in the five years to November 2018 (2.2%) was significantly less than the average recorded in the previous five years (3.3%).

2. New car sales keep going downhill

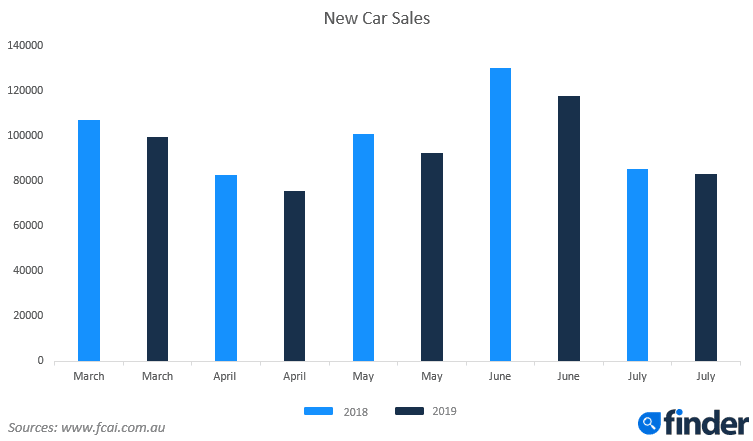

For 16 months in a row, the Federal Chamber of Automotive Industries has reported declining month-on-month sales figures. This means that sales were lower than the previous year for every month between April 2017 and March 2018. From April 2018 on, sales dropped further, resulting in lower figures than the previous year.

If wage growth slows and families have less to spend, a new car is often the first thing struck from a family budget. This is why new car sales are seen as a barometer of the health of a country's economy. In the three years leading up to the global financial crisis of 2008, new car sales in the US dropped from 16 million per year to 10 million. This consistent decline in Australia could be ominous.

3. Very few properties are going up for auction

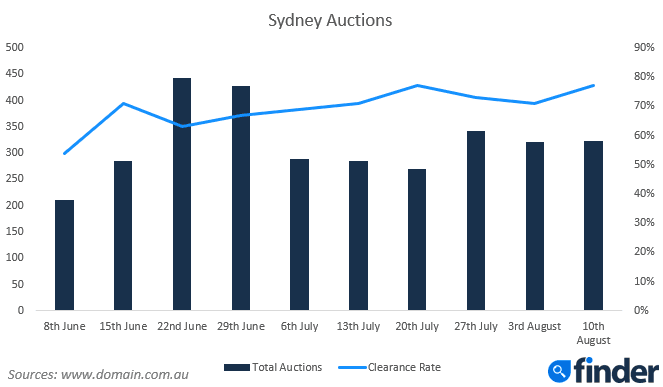

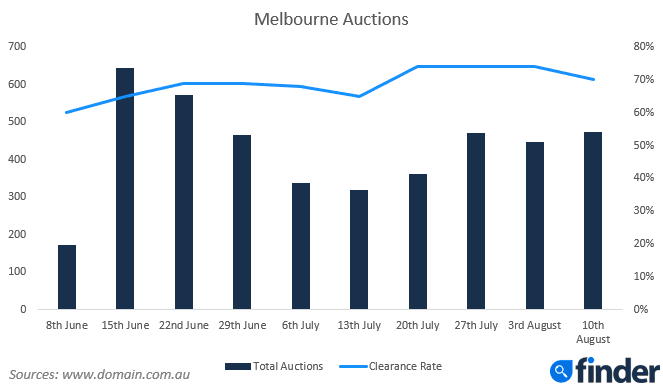

While house prices in some cities have started to recover slightly after months of decline, they are heavily influenced by the low volume of housing stock on offer. A 71% auction clearance rate in Sydney on 3 August this year may look healthy, especially when compared to the 52% clearance rate in the same week in 2018. However, only 322 actual auctions took place on this date in 2019 versus 381 in 2018 and 503 in 2017.

These low numbers indicate that homeowners are still rather reluctant to sell, with homes staying on the market for longer. If the volume of available stock on the market increases too quickly, this could apply downward pressure on price. It's a delicate balance: homeowners and prospective buyers should keep a close eye on price, clearance rates and volume in the coming months.

4. More homeowners are defaulting on their loans

Moody's Australian Mortgage Delinquencies report, released in April this year, found that the proportion of Australian residential mortgages that were more than 30 days in arrears increased from 1.45% in the 12 months leading up to November 2017 to 1.58% by November 2018. Delinquencies increased in all states except Queensland. Further, Moody's predicts that "Mortgage delinquencies will continue to increase over 2019, because of high debt levels, subdued wage growth, the conversion of a large number of interest-only mortgages to principal-and-interest loans and declining house prices".

However, Moody's also points out that these delinquency rates remain relatively low overall. Still, the trend for this statistic is definitely going in the wrong direction.

5. Australia's loan book is seriously risky

Eddie Hobbs, an Irish financial commentator who was one of the few to predict the housing market crash of 2007/8, has painted a grim picture of Australia's loan book in two recent articles for the Irish Examiner.

First – a bit of background. Mortgages are divided by lenders into two categories: "prime" and "subprime". A prime mortgage usually indicates a loan that the borrower will have little difficulty paying back. This means that they borrowed less than five times their annual earnings and that the repayments for the loan will cost less than 30% of their monthly income. A subprime loan is one where these criteria have not been met. It usually means the borrowers will struggle more to pay back the funds borrowed and the loan is a riskier endeavour for the bank.

To reflect this risk, subprime loans often have a higher interest rate than prime loans. Banks can, in theory, make more money from these type of loans as long as the buyer is able to repay them. However, these borrowers tend to be 2-5 times more likely to default than prime borrowers. In fact, it was these subprime loans that caused the GFC in the first place, with high numbers of borrowers in the US unable to repay loans they should never have been offered.

Australian banks currently classify all of their loans as prime. Hobbs's view is that these loans are being misclassified. He argues that 40% of Australia's loan book is subprime or non-prime because they do not meet the two criteria mentioned above.

Hobbs also points out that 40% of Australian mortgage holders are on interest-only loans. These loans, where the borrower pays only the interest on the loan for a fixed period of years, with the aim of selling the property for an increased price after that period ends, are generally aimed at investors. Products like this only make sense while house prices are increasing. Falling prices mean that borrowers are failing to pay off the capital on a loan for an asset that is decreasing in value – they are losing money hand over fist. It's worth noting that once the interest-only period runs out on these loans, the borrower needs to move over to principal and interest payments, which are significantly higher. At this point, with repayments increasing and the property in negative equity, there is significant pressure on investors to default.

Finally, one-third of Australia's loan book is made up of buy-to-let investor properties, with a huge 80% of these loans being interest only. The same figure in Ireland just before the GFC was only 15%, with half of those being interest-free.

Investors tend to be far more likely to default once the penalties of doing so outweigh the money being lost on an investment. Owner-occupiers, on the other hand, will generally do anything they can to keep their home. It is for this reason that the high prevalence of investor and interest-only properties in the Australian market means Australia's housing market could be in a far more precarious position now than Ireland's was before the recession. With the right set of glasses, everything tends to look rosy until all of a sudden it doesn't.

6. Retail sales are at their weakest since 1991

Australian retail spending is down, with the current volume of sales reaching levels not seen since the early 90s, according to a recent NAB report. While recent retail figures for June show slightly more positive growth than May, growth is still stubbornly slow in this sector. With both NAB and Westpac economists talking about "recessionary levels" of spending, the big retailers will be keeping a close eye on these trends.

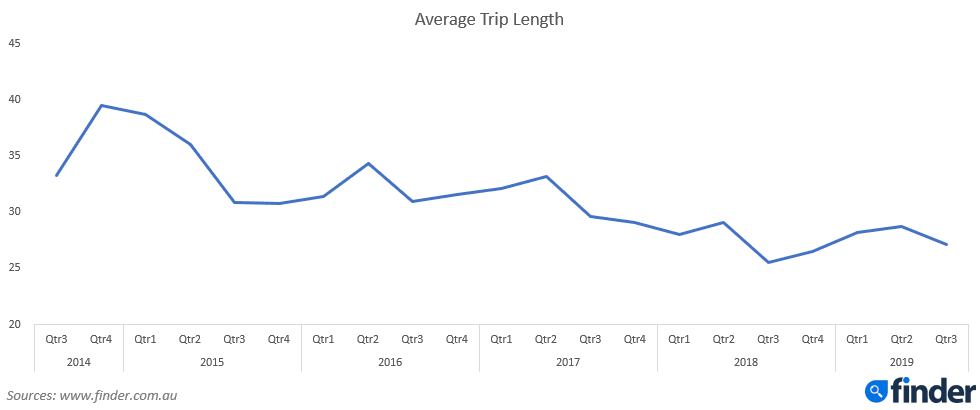

7. Australians are looking to book shorter holidays

Analysis of travel insurance quotes obtained via Finder's travel insurance engine shows that the number of days Aussies are intending to travel has been falling. With users able to obtain quotes for up to one full year of travel, the average number of travel days quoted has declined steadily from around 40 days in the last quarter of 2014 to only 27 days in the current quarter.

8. Global economies are teetering on the edge of recession

With $58 billion (and counting) wiped off the Australian stock market today, 800 points shaved off the DOW, 2.9% being shed from the US's S&P 500, and the German economy slipping back into negative growth, global financial markets look pretty grim across the board. With Boris Johnson's hard-line on a no-deal Brexit threatening to place a serious financial burden on both the UK and the EU, things could be set to get a whole lot worse.

9. People are ditching credit cards in record numbers

The number of credit cards in circulation in Australia has fallen by nearly a million, from 16.7 million cards in December 2017 to 15.8 million in June 2019. Over the same period, the average purchase value has fallen from $116 to $112, while the average outstanding balance costing interest has increased, from $1,930 to $1,972.

While there are several factors driving this decline – including the rise of buy-now-pay-later services such as AfterPay and ZipMoney, and the increasingly good value offered via $0-annual-fee debit cards from the likes of ING, ME and U Bank – the declining number of credit cards could also be seen as an indicator of households tightening their financial belts.

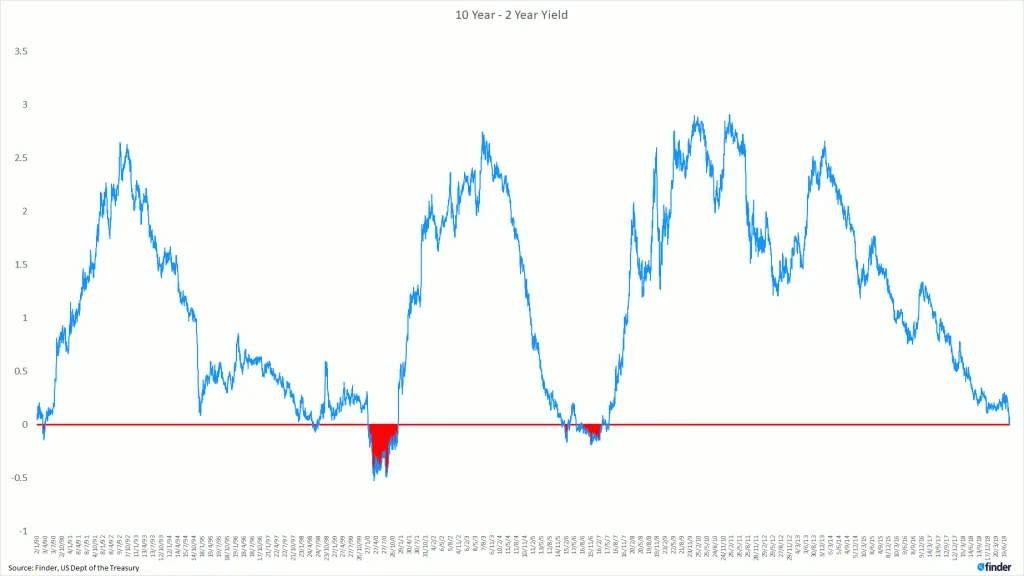

10. Both the US and Canada's yield curve just inverted

A "yield curve" describes the usual behaviour of returns on investments in government bonds, with longer bond terms usually offering higher returns. However, in time of economic uncertainty, investors tend to invest more heavily in low-risk government bonds than more risky options like the stock market and housing. If there is enough of an investment wave, this can have an odd effect on returns.

An inverted yield curve occurs when the returns on long-term investments become lower than the returns on shorter-term ones, suggesting a slowing economy to come. For more on this, you can't do better than reading this piece from our investments editor Kylie Purcell.

11. Gold is soaring

Gold prices are at record highs. This tends to be the mineral of last resort for those looking to invest in a stable commodity in rocky seas.

12. And finally… the economy is already in per-capita recession

Australia entered a technical per-capita recession earlier this year, which means that Australia gross domestic product per person has decreased for two consecutive quarters. While not indicating a recession directly, this essentially means that the economy is not keeping up with Australia's population growth.

-

So there you have it – 12 indicators that show we are absolutely, definitely heading for a recession. But before you start to panic it's important to remember every coin has two sides. Next time (well if we last that long), I'll be taking an equally close look at the solid reasons why Australia will not be heading for a recession in 2020.

Be sure to check back then for the other side of the story, so you can make up your own mind.

Graham Cooke's Insights Blog examines issues affecting the Australian consumer. It appears regularly on finder.com.au. For regular updates check out twitter @gcooke42.

Picture: Getty/Shutterstock

Ask a question