IMF: Cryptocurrency stablecoins will likely put some banks out of business

The International Monetary Fund welcomes you to the age of digital currency.

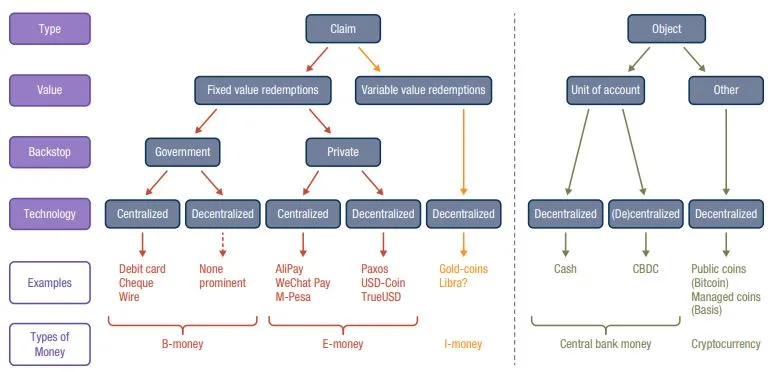

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently released a new paper, The Rise of Digital Money, outlining a cryptocurrency-inclusive "money tree" and explaining how it expects the rise of digital currencies to impact existing institutions.

In particular, it's expecting e-money to start pressuring banks into evolving their own products and services. But to understand what e-money actually is, it's worth running through the money tree, as a useful way of highlighting how different currencies and digital currencies lend themselves to different applications and occupy different positions in the money tree.

Here it is:

The Rise of Digital Money

Row by row

B-Money, e-money, i-money, central bank money and cryptocurrency

Based on this money tree, the IMF suggests different categories of money emerging in the digital age, each with its own pros and cons.

| Money | Features |

|---|---|

| B-Money (Bank money) Eg: USD credit card payment |

|

| E-Money (Electronic money) Eg: Paxos, M-Pesa |

|

| I-Money (Investment money) Eg: Gold-backed stablecoins, tokenised shares |

|

| Central Bank Money Eg: USD, EUR |

|

| Cryptocurrency Eg: Bitcoin, Dai |

|

As you can see, this framework makes it easier to directly apply comparisons between new digital currencies and existing payment systems in the context of their actual applications and the benefits they deliver for users.

Competing currencies

The main form of existing currency is b-money, making up the bulk of payments. If any digital currency can disrupt it, it's probably going to be e-money, the IMF suggests, based on the fact that it shares the same highly-desirable characteristic of being redeemable at face value.

One of its main advantages, however, is that possession of the e-money digital asset itself proves ownership of a fixed portion of the backing assets, which means it can be transferred more efficiently.

Consider the following unnecessarily simplified examples to see what this actually means:

Buying a loaf of bread with b-money

The number in your bank account represents your claim to a portion of your bank's assets. When you buy a loaf of bread with an electronic payment, your bank checks that you are entitled to at least one loaf of bread's worth of its assets, and then earmarks that much for transfer to the baker's bank.

At the end of the day, your bank will send your money to the baker's bank as part of a bulk transaction. This is an "interbank settlement".

To make these "interbank settlements" happen, all the big banks need their own separate payment layer, and a system which has developed differently in different countries. In the USA, the primary system is CHIPS. This is a separate company, jointly owned by all the big banks. Its job is to say things like:

"This bank owes that bank $1 billion, while that bank owes this bank $800 million. Therefore this bank should pay that bank $200 million and we'll call it even." It then handles the payment.

These clearinghouses are often separate companies with their own employees, company health insurance and all that goodness, which means that it needs to extract revenue from the banks, who in turn need to extract more revenue from their customers. Other downsides include the potential for cartel behaviour among the owners of a country's clearinghouse.

And this is just for domestic payments. Cross-border payments are an entirely more complicated affair because banks need to connect across completely different systems.

This is what the IMF means when it says that b-money depends on extremely complex back-ends. And this extremely complex back-end is why it's socially acceptable to point and laugh at people who say digital currency is pointless just because they can instantly pay for a loaf of bread with their credit card.

Buying a loaf of bread with stablecoin e-money

You transfer a digital asset directly to the baker. The amount you send is worth precisely one loaf of bread, and once the baker has possession of it, they are entitled to one loaf of bread's worth of the redeemable asset.

Like b-money, the e-money can be redeemed, but there are increasingly few reasons to ever do so as long as everyone trusts its backing. As long as you trust your bank, you don't need to cash out your entire bank account and put it under your mattress. For the same reason, as long as you trust M-Pesa or USDC, you don't need to cash out your M-Pesa account or redeem your stablecoin.

Simple ownership of the digital asset itself proves one's entitlement to a set portion of the backing assets. Because the transfer is instantaneous and directly from you to the baker, there's no need for a bank or the e-money backer to lift a finger, there's no need for a central clearinghouse and there are no frictions in cross-border payments, as long as the e-money's backing is equally trusted and it's equally redeemable on both sides of the border.

Plus, object-style cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, and other decentralised value-bearing digital assets, can help ensure that the future arrives punctually by allowing for the storage of value entirely outside the existing banking framework.

If regulatory concerns mandate that stablecoin-type e-money has to be collateralised by value stored by the banking system, stablecoins can simply turn around and present a more cost-effective product by collateralising with cryptocurrencies instead – albeit at the cost of some stability.

For these reasons, the IMF expects e-money to put pressure on the existing banking system.

Why e-money will happen

So if e-money cannot be as stable a store of value as b-money or central bank money, could its adoption still take off? The answer is yes, due to its relative attractiveness as a means of payment. Clearly, this will depend on country circumstances and the technological advancements adopted by banks to improve the convenience of b-money.

"Banks will feel pressure from e-money but should be able to respond by offering more attractive services or similar products," the IMF suggests. "Nevertheless, policymakers should be prepared for some disruption in the banking landscape."

"The two most common forms of money today will face tough competition and could even be surpassed. Cash and bank deposits will battle with e-money – electronically stored monetary value denominated in, and pegged to, a common unit of account, such as the euro, dollar or renminbi, or a basket thereof."

The exact level of the benefits provided by e-money will vary depending on how it works, and different systems will remove different amounts of overhead from that complex back-end that supports all claim-type currencies. Consider some of the frictions remaining in e-money systems that don't use actual digital currency.

M-Pesa

- Users have a digital M-Pesa account tied to their phone number.

- Users make cash deposits and withdrawals from M-Pesa accounts via third-party agents.

- Users can send money via text message.

- The currency itself is a claim on a portion of the M-Pesa money pool. M-Pesa just appropriately allocates the money on the back-end.

When M-Pesa first launched, it faced strong opposition from Kenya's banks, which accused it of basically being an unlicensed bank. Today Kenya's regulations around mobile money services require them to secure customer funds across several different "strong" rated banks once above a certain threshold of funds held.

As such, the system removes a lot of overhead at the immediate point of sale, but it is still partly enmeshed in the web of interbank costs and challenges.

WeChat Pay and AliPay

- Users have accounts connected to phone numbers and related social media platforms.

- Users can make mobile payments via apps.

- The currency itself is a claim on a portion of the tech company's money pools.

Until recently, both companies held all their customer funds in their own respective Tencent and Ant Financial arms, through which they'd earn interest on customer funds without always paying any back to consumers. This theoretically put customer funds at risk, while simultaneously making WeChat and AliPay supremely unpopular in the banking industry.

Consequently, China's central bank has mandated that WeChat Pay and AliPay are now required to store customer funds in non-interest bearing accounts at the central bank.

Unlike M-Pesa, it avoids the frictions of the wider banking network by being tied directly to the central bank. But it's also completely unsuitable for international payments, which will naturally restrict the possible growth of these payment mechanisms. It can't integrate non-CNY payments without many additional downsides, and countries have started taking the natural step of banning AliPay and WeChat to prevent Chinese tourists from sidestepping the local economy.

Can i-money be currency?

On one level, it sounds patently ridiculous that i-money, or money that can be redeemed for a variable value, could be used as a currency. Who would buy an apple with AAPL?

Besides, the same economists who repeatedly say that Bitcoin does not fulfil the requirements of a currency (store of value, means of payment, unit of account) will be quick to point out that something which can only be redeemed for a variable value is immediately leaning away from the strict definition of money.

The IMF is less deterred and suggests that the ones backed by the safest and most liquid assets, such as Libra, could indeed become money if widely accepted.

"Whether or not i-money is actually a form of 'money' is open for debate," it says. "To economists, money is a stable store of value, a widespread means of payment and a unit of account. No generally accepted legal definition exists, though most emphasise the ready exchange into currency, as well as denomination in a unit of account and widespread acceptance as a means of payment."

"Most likely, there would be a continuum of i-monies depending on the assets backing these. Those backed by the safest and most liquid assets, if widely accepted, could be considered a form of money."

Of course, although variable redemption value may be a concern for currency holders, it doesn't really impinge on transactions too much. The wonders of technology mean that you no longer have to whip out a calculator and work out the exchange rates when making a transaction, and it's easy enough to simply convert i-money into the correct amount of fixed-value money at the point of sale. But this is still a cost that e-money doesn't intend to worry about, which makes the more volatile i-money a less competitive option against e-money and b-money.

That said, it's still worth thinking about i-money in a wider sense of the word than the term "investment money" would suggest.

For example, electricity-backed cryptocurrencies – as in, i-money that can be redeemed for a certain amount of electricity at current market prices – would fall under the category of i-money even if you don't consider it an investment. In situations such as autonomous electric vehicles making payments to other autonomous electric vehicles, data centres and other robots while crossing international borders, it might make more sense to simply denominate inter-machine payments in joules rather than dollars.

What about cryptocurrency and CBDC?

It's in this framework that central banks are juggling their obligations, the foremost of which is to not collapse the global economy.

The general population is tapped into b-money, and b-money is tapped directly into central banks, which lets them yank all the bells and whistles that keep the world turning. But e-money severs that connection. It puts intermediaries with their own reserves between central banks and the end users, diminishing their economic control with potentially unexpected results.

"One solution is to offer selected new e-money providers access to central bank reserves, though under strict conditions," the IMF hazards. "Doing so raises risks, but it also has various advantages. Not least, central banks in some countries could partner with e-money providers to effectively provide CBDC... We call this arrangement 'synthetic CBDC'."

China provides a leading example here. Its two mobile payment giants, Alipay and WeChat Pay, are both already required to hold client funds at the country's central bank, while the central bank itself is working on a digital currency.

But if there's one thing the IMF is sure about, it's that change is coming.

Payments are a social business, not a financial business

Network effects are likely going to drive change much faster than people expect, the IMF says.

"Economists beware! Payments are not just the act of extinguishing a debt. They are an exchange, an interaction between people – a fundamentally social experience. If two people use the same payment method, a third is more likely to join. And, yes, payments can be fun, more fun, at least, in e-money and i-money than in paper bills. Emojis, messages and photos, or perhaps a customer rating, cannot be sent with a mere debit card payment!"

Payments are a social experience, the IMF says, and tech giants are experts at providing social experiences while banks are not. It's no coincidence that recent counter-crypto initiatives in the USA include measures specifically targeted at tech companies that specialise in social experiences.

The IMF isn't really entertaining the idea that banks will lobby their way out of disruption forever.

"Will banks adapt fast enough? Can they live and breathe online customer satisfaction, user-centred design and integration with social media the way big techs do? Are they sufficiently agile to change business models? Some will be left behind, no doubt. Others will evolve, but must do so quickly."

It's easy to see how the regulatory environment will be a key element in determining the future of money, how entire countries and industries could quickly be left behind if they don't lean into the opportunity of digital currency, and why Libra's arrival means that CBDC is suddenly a hot topic after spending some time on the backburner.

You can also see why banks have every interest in pushing back against the intrusion of tech companies in their industry until they can release their own stablecoins, but you can also see why some banks will be fundamentally unable to match the user experience provided by social media giants.

What's next?

Although there are no guarantees, the IMF suggests that the most likely future is a prolonged struggle between b-money and e-money, where both banks and tech companies leverage existing user bases (Facebook's ~$20 billion WhatsApp purchase makes a lot more sense in this context) and their other strengths.

Tech companies can wield the strength of providing superior social user experiences and much easier cross-border payments, it suggests, while banks can offer a wider range of financial products to end users and serve e-money providers as clients further up the supply chain.

As e-money gains traction, the IMF expects the natural introduction of CBDC as a way for central banks to retain economic control.

Anyone trying to predict the relatively near-term future of the financial industry right now would probably be well served by keeping an eye on the places where banks are losing their remaining advantages. Specifically, the developing field of decentralised finance (DeFi) and the paired rise of object-style cryptocurrencies combined with regulatory environments that free tech companies from needing to rely on banks.

Also watch

Disclosure: The author holds BNB and BTC at the time of writing.

Latest cryptocurrency news

-

The Coinstash Cryptocurrency Hub

30 May 2024 |

-

Ordinals and runes – the new crypto craze?

24 Apr 2024 |

-

Join the party: Finder’s giving away $200K worth of Bitcoin

23 Feb 2022 |

-

Australians have spent $50.9 million on crypto trading fees

31 Jan 2022 |

-

Stablecoins vs Bitcoin: What’s the difference?

3 Nov 2021 |

Picture: Shutterstock

Ask a question