Waterfall authentication, the Consumer Data Right and passing the barbeque test

How CDR should approach authentication to benefit all Australian consumers.

Up and down the country this summer, Australians will start to use the newly created Consumer Data Right (CDR) regime to share their data. This game-changing piece of legislation has been many years in the making. Here at Finder, we're excited about its potential to help people make better decisions. As the whole scheme is opt-in, this means it will only be helpful to consumers if they choose to use it.

In this article, I'll make a case for a rethink on authentication for the CDR so we can make sure that the CDR passes the "barbeque test".

What is the barbeque test?

I always think that a good litmus test for how useful something will be, is to see how easy it is to explain at a barbeque with friends. The CDR can be accessed on your smartphone, so you can ace the barbecue test by walking your friend through it in real time on your phone while you explain it.

If you get this right, you'll help build advocates for the CDR that will add to its uptake. Right now, I think the authentication method for the CDR is the crucial factor that will bring on more advocates.

What is authentication and what is the current CDR authentication flow?

To zoom out, authentication is the stage of consumer onboarding where the user confirms who they are in a way that matches a company or organisation's records.

In many scenarios, this step is the final frontier for the consumer. They're ready to go, they've given the necessary consents and they want that great experience. The authentication process should be seamless and require minimal steps to keep users engaged. If the authentication process requires too much extra work, then many will simply drop out.

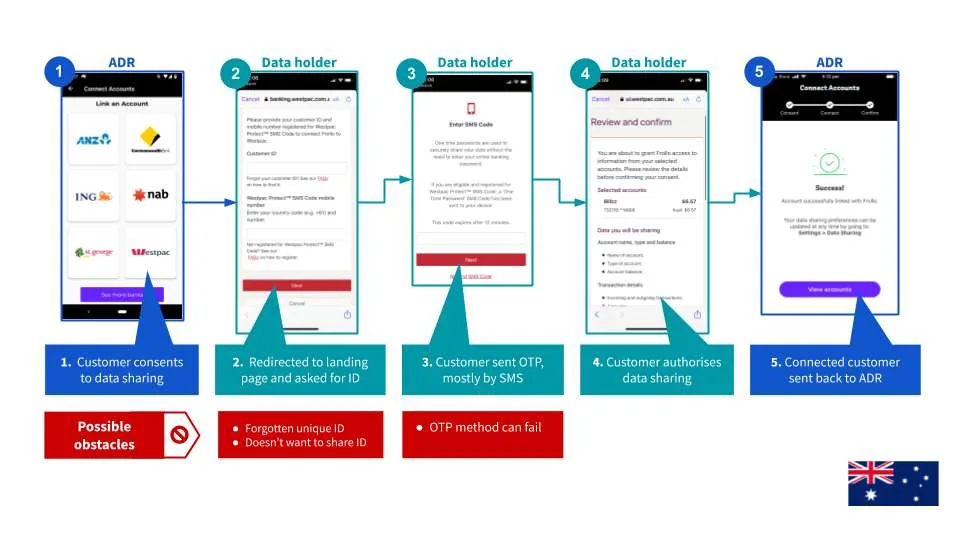

The current CDR authentication process relies on a one-time password (OTP) being sent to the consumer. This model causes some obstacles straight away. In many instances, people may not remember the unique identifier needed to start the one-time password flow. Others simply may not want to share this login information with another party.

We have also seen first-hand instances of where the OTP delivery method just fails and the consumer doesn't receive the OTP through the correct channel.

Lessons from abroad: What can we learn from the UK?

Australia is not the first country to roll out a framework to encourage data sharing in the banking space – or "open banking" as it is often called. The UK launched its own version of open banking over two years ago, and there's a lot that we can learn from it.

On authentication, the UK has a more principle-based approach, with a set of minimum requirements for what constitutes its definition of "Strong Customer Authentication" (SCA). This SCA approach requires the consumer to provide two out of three of the following for authentication to occur:

- Something they own (e.g. access to a particular mobile device)

- Something they know (e.g. a password or pincode)

- Something they are (e.g. their fingerprint or faceID)

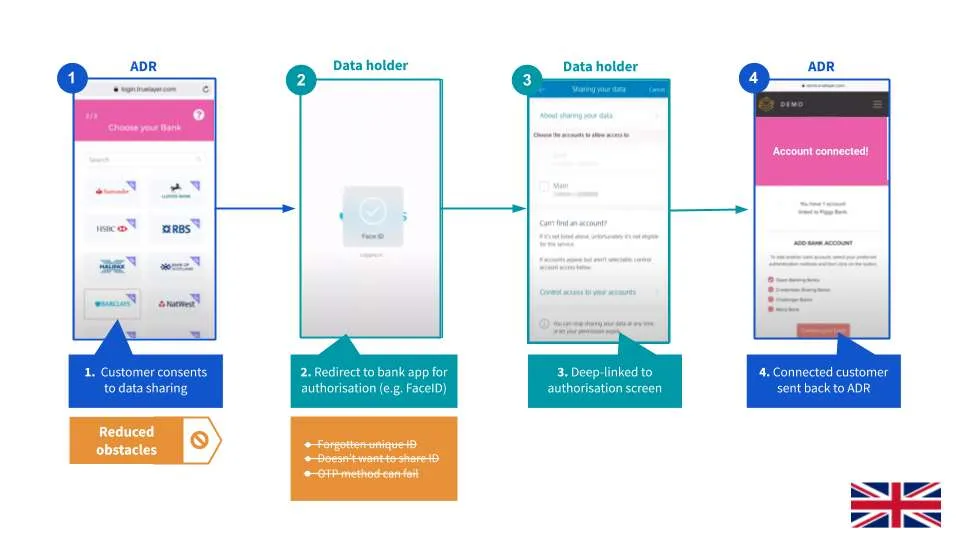

A high proportion of UK consumers now access their online banking through an app on their smartphone. This makes achieving strong customer authentication simple for the user.

The consumer agrees to share their banking data and is then deep-linked into their banking app. From here, they log into their app using their usual method (e.g. fingerprint or FaceID) and then agree to share their data from within their trusted banking app.

The key thing that makes this process both more secure and user friendly is the use of biometrics. Biometrics are unique to an individual (e.g. their fingerprint). This means the person doesn't need to remember their login IDs. It also cuts out any risk that a one-time password could be intercepted.

These types of biometric logins have already been adopted by pretty much every banking app in Australia. A recent study from Lastpass found that 64% of Australians trust fingerprint or facial recognition more than traditional passwords.

There's also growing evidence from the UK that app-to-app authentication flows in the open banking scheme offer a user experience that's far more likely to be successfully completed.

One intermediary that operates in the UK, Truelayer, found that the proportion of customers that are successfully able to connect their bank account using open banking increases by 33% for app-to-app flows when compared to other authentication methods. To me, this is clear evidence that app-to-app flows work better for consumers.

How do we move forward with app-to-app authentication?

I sit on the two advisory committees that are helping the Data Standards Body introduce the CDR to both the banking and energy sectors in Australia. Earlier this month, I presented these views on app-to-app authentication to those groups and made a couple of suggestions for how I would change things.

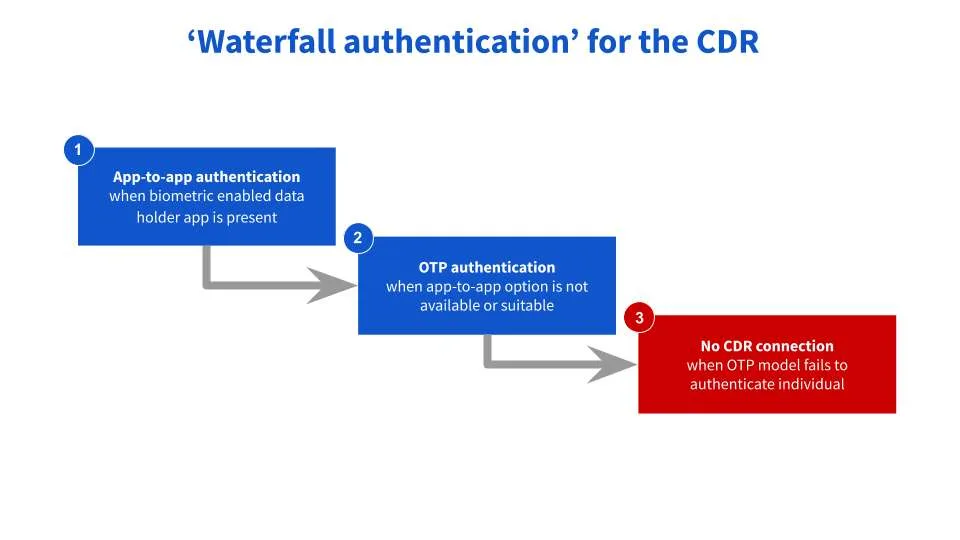

My key proposal here is to move towards a "waterfall authentication" model. This would mean that app-to-app authentication would become the preferred method for the CDR when it is available, and that biometrics would be enabled.

This could either be optional for data holders that are ready to move to this process or mandated like it is for the nine biggest banks in the UK. Either way, I think it's clear that app-to-app flows offer an experience that's easier for consumers to navigate, while also adding an additional layer of security.

One issue raised in the committee meetings was that not all customers have access to an app when they want to share their data within the CDR. This is particularly relevant for the energy sector, which is where the CDR is coming next. Digital engagement in this space is much lower.

It is for exactly this reason that I am calling for a "waterfall authentication" model, where you can create alternative authentication options for when app-to-app is not available. In these instances, for now, we should flow down to stage two of the waterfall where the current one-time password model comes into play.

The CDR has made a lot of ground in a short amount of time. But now is not the time to sit on our laurels. We need to continue to build on the current standards to unlock innovation that exceeds customer expectations both today and in the future.

I believe that the tweaks suggested above will allow for a better user experience that we would be happy to show off at a barbeque. Importantly, it would also set a precedent for introducing future technology that we can't yet imagine, which could be the preferred option for consumer authentication in years to come.

Ask a question